Someone at US Ends.com suggested, when posting a photo of a similar sign on eastbound I-70, that there is one speed limit for regular travelers and a second, lower speed limit for dust storms.

I took this photo in 2006 on I-70 in Utah, while MOH and I were traveling in an easterly direction. The sign was located near Cisco (location way below), and it's apparently no longer there, or anyhoo it isn't shown on the current rendition of Google Street View. The Colorado River is less than 10 miles to the south of the interstate, and one happens to be driving through an upland largely underlain by Mancos Shale, which often makes paved roads lose their originally smooth surface, leaving drivers and passengers alike to feel about the same as they would while driving over bad frost heaves on the Alaskan Highway between Destruction Bay, Yukon, and Tok, Alaska.

Anyway, this is my first post in an off-and-on series of Thursday road sign posts. Many of the signs I've photographed over the years are standard mileage signs, exit signs, warning signs (curves, low flying aircraft, what-have-you), regulatory signs (stop, yield, do-this, do-that), mileposts (often photographed so I'll know where a certain roadcut or outcrop was located along the road), and other signs, some of which have nothing to do with the road (Iditarod signs, pub signs, signs on and inside buildings): anywhere signs, in other words.

Thursday, June 30, 2016

Tuesday, June 28, 2016

Approach to Titus Canyon: To Red Pass

|

| It looks to me like you can see Quail Rock from White Pass! |

The geology changes a little at the unnamed pass, and the road goes into a series of curves, while also going up and down quite a bit. We've entered the territory of the Tertiary Titus Canyon Formation. The exposures right along the road from here to Red Pass will be either Titus Canyon Formation or Cambrian formations, though not much of the latter, and none that I have photos of.

This photo looks up the western branch of the western fork of upper Titanothere Canyon (Titanothere Canyon is not actually divided into forks and branches, but I've got to call them something!). A fault runs up this canyon, dropping the Tertiary section downward on the northeast (right) side.

You can see the southeast-northwest trending fault in this geologic overlay I made on Google Earth (G.E.). The geology is from Niemi, 2012. Using the "Add Path" feature of G.E. creates lines that hang up in the air above the topography in places, making the contacts as drawn look a little ragged. They also disappear behind topography, going in and out unexpectedly in places, so they are best used for quick visualization. My drawing of the contacts may not be precise, as Niemi's geologic map wasn't associated with an air photo (as published, anyway), and his topo base was digitized somehow, so it doesn't correlate directly with USGS topographic maps (TNM 2.0 Viewer), which can be directly correlated with air photos. I also may have modified some contacts based on what I was seeing on the air photos (G.E.).

Here, above and below, we can begin to see a little of the geology, including a lot of Quaternary alluvium (Q). Notice the terraces of older alluvium, especially the nice one up the canyon. And, by the way, I use blue for faults.

in my last post. Briefly, the Trp is the Miocene Rhyolite of Picture rock, a rhyodacite to latite flow; the Tw is the Miocene Wahguyhe Formation; the Tg is the Miocene Panuga Formation; and the EOgtc is the latest Eocene to Oligocene Titus Canyon Formation. What is shown as Tg in these posts (and on Niemi's map) was once considered to be the upper part of the Titus Canyon Formation, a section known as the Green Conglomerate facies, which sits atop a disconformity on the Variegated facies of the Titus Canyon Formation, formerly considered to be the middle unit of the Titus. All that changed with the publication of Snow and Lux's Tectono-sequence stratigraphy of Tertiary rocks, California and Nevada in 1999, when the Green Conglomerate facies was assigned to the Panuga.

Below, you can see the sort of thing one can work with if geologic contacts are transferred to Google Earth.

|

| This map is a small portion of Niemi's 2012 geologic map of the central Grapevine Mountains. |

We're getting closer and closer to Red Pass. MOH and I decided to pull over in a slightly wide spot near the next curve so we could hike around a little and look at rocks. I took the next photo just before that curve, primarily to grab a shot of what appears to be an example of two normal faults forming a small, asymmetrical graben on the hill beyond the curve.

|

| Is this a small graben? |

|

| A closer view of the hypothetical graben. |

|

| The two hypothesized faults, as seen from a different angle thanks to G.E. The lower, lighter cyan line marks the base of the crystal tuff seen in the last photo. |

|

| A bit of the Titus Canyon Formation, I'm not sure which part. |

|

| We're looking in a southerly direction at the main switchback going up Red Pass. You can see why it's called Red Pass! |

With this next photo, we've begun to climb the east side of Red Pass. We turn back around, after pulling over to the side, to see where we've been. The unnamed pass is right at that little white bit of road nearly at the center of the next photo. Just below that section of road, you see the Cambrian part of the latest piece of our journey: The jagged reddish brown rocks on the right side of the photo (south) are Cambrian Zabriskie Quartzite dipping northward (left), overlain by a thin, dark gray section of rock mapped as Cambrian Carrara Formation (although on G.E. the rock looks about the same as the Cambrian Bonanza King Formation did near White Pass).

|

| We're looking northeast into the part of upper Titanothere Canyon. |

A Few References:

Lengner, K., and Troxel, B.W., 2008, Death Valley's Titus Canyon & Leadfield ghost town: Deep Enough Press, 175 p.

Niemi, N.A., 2012, Geologic Map of the Central Grapevine Mountains, Inyo County, California, and Esmeralda and Nye Counties, Nevada: Nevada, Geological Society of America Digital Maps and Charts Series, DMC12, 1:48,000, 28 p. text.

Snow, J.K., and Lux, D.R., 1999, Tectono-sequence stratigraphy of Tertiaryrocks in the Cottonwood Mountain and northern Death Valley area, Californiaand Nevada, in Wright, L.A. and Troxel, B.W. eds., Cenozoic basinsof the Death Valley region: Geological Society of America Special Paper 333, p. 17–64.

Related Posts:

Beatty: Old Buildings, A Fold, and Onward toward Titus Canyon

The Approach to Titus Canyon: Amargosa Narrows, Bullfrog Pit, and the Original Bullfrog Mine

Mineral Monday: Close-Ups of Bullfrog Ore from the Original Bullfrog Mine, Nevada

The Approach to Titus Canyon: Tan Mountain

The Approach to Titus Canyon: Up and over White Pass

Location:

Red Pass, California, USA

Labels:

california,

d.v.,

fossils,

geography,

geology,

maps,

parks,

road trip,

roadside,

sedimentary rocks,

tertiary,

titus,

volcanic rocks

Tuesday, June 21, 2016

Approach to Titus Canyon: Up and Over White Pass

Getting past Tan Mountain on the trip down the Titus Canyon road always feels like a milestone to me, not so much because the road gets better—it maybe does get better, for a while, or maybe I just get used to the washboard—but because I've finally made it past the Amargosa Desert into the Grapevine Mountains. (The Grapevine Mountains are part of the much larger Amargosa Range, the mountains that essentially bound the east side of Death Valley. See the image after these two bush photos.)

On this section of our trip, we are not actually in Titus Canyon: We are in some unnamed wash that drains eastward into the northwest part of the Amargosa Desert. Beyond "White Pass," we will at first be in the upper reaches of Titanothere Canyon, still not in Titus Canyon.

I suspect this bush, growing beneath the hoodoos of Tan Mountain, is Purshia stansburyana (formerly P. stansburiana) rather than its close cousin P. tridentata—Lengner and Troxel (2008) show pictures of this bush growing along the road near Tan Mountain. It's hosting what they identify as the caterpillars of the Fotis hairstreak (Callophrys fotis).

Well, I've torqued this G.E. image around quite a bit, so that the long dimension is parallel to the NW-SE California-Nevada stateline. I've added a crude outline of the Grapevine Mountains, the portion of the larger Amargosa Range that runs essentially from the Daylight Pass Road on the southwest (far left boundary) to Scotty's Castle on the northwest (far right boundary that has tailed upward). The odd shape of the mountains on the right occurs because at about Grapevine Peak, the mountain range as named on maps splits in two, with a little tail running WNW toward Scotty's Castle in California, while the main part of the range runs ENE toward Bonnie Claire and Scotty's Junction in Nevada. If you look closely, I've marked White Pass and Red Pass, and a couple faults. (I hope to talk about these faults in a later post.) If I hadn't torqued the image, it would have looked like this:

"White Pass" as a name is well established in Titus Canyon and Death Valley lore: It's mentioned on several websites, including the NPS's page about Titus Canyon, although it's shown on zero maps (that I could find) and is not listed as a place name by the USGS. Consequently, you not only get a location on the Google My Maps map way below, I'm giving you the location on a topo map:

White Pass will mark another official milestone on our journey: We will enter the realm of this fairly detailed geologic map. Yay!

Between Tan Mountain and White Pass, the road runs south of several smallish dark brown hills composed of brown volcanic rock above white to pale yellow sedimentary rocks, often tuffacaceous, with intercalated tuffs. The brown, hill-capping formation has been mapped as Tlt, Lithic Ridge Tuff and related felsic rocks, by Workman et al (2002) and as part of Tw, the newly defined Wahguyhe Formation, by Niemi (2012). So it's a little confusing, but with a little research I determined that these brownish cliffs are indeed what has been called a latite flow before (Lengner and Troxel, 2008), with Niemi saying that the latite (he included it in the Wahguyhe) correlates with the Rhyolite of Picture Rock, which is rhyodacitic to latitic. So, when you look north at the dark brown caps, think rhyodacite to latite!

Moving on, we arrive at White Pass, where we can now see into the northeasternmost part of Titanothere Canyon.

At White Pass, and in fact all along the road from about a mile past Tan Mountain, rocks to the south are all Cambrian while rocks to the north are all Tertiary.

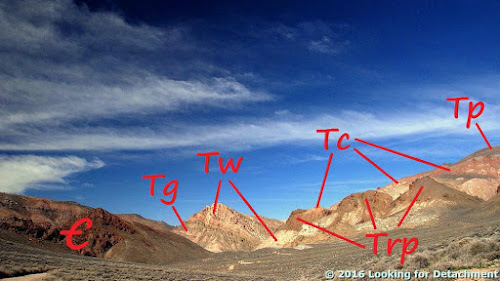

We'll see more of the Cambrian in a bit. The Tg is the Panuga Formation. Probably some of you will notice that this greenish unit has been included in the Titus Canyon Formation before. We'll see more of this unit on the way to Red Pass, and maybe we'll figure out whether it's Titus Canyon Formation or not. The Wahguyhe Formation (Tw) includes various sedimentary and volcanic units, including sandstone, shale, conglomerate, and tuffs. In places, the Trp, Rhyolite of Picture Rock, often described as a latite flow, is included in Tw. Here I've broken it out as best as I can (and hopefully, correctly!). Overlying the Tw and Trp are various tuffs, mostly ash-flow sheets from the southwest Nevada volcanic field, including those in the Crater Flat Group (Tc), the Paintbrush Group (Tp), and the Timber Mountain Group (Tm, not shown in these photos). All these Tertiary formations are Miocene in age (Niemi, 2012).

Before leaving White Pass, we'll look off a little to the south. These two photos were taken about 7 years apart from almost the same spot. The lighting and clouds are a bit different, the time of day is nearly the same.

I guess I'm often inspired by the same rocks and the same angles! The photos both show Thimble Peak (6,381 ft, 1945 m), the thimble-shaped peak on the far left. The dark gray rocks in the foreground on the left are in the Bonanza King Formation; the dark reddish brown rocks in the foreground, center and right (in shadow in the 2nd photo), consist, I think, of the Zabriskie Quartzite; and the layered rocks in the distance consist of the Bonanza King Formation (the gray on Thimble Peak and the dark gray capping the ridge to the right of Thimble Peak) overlying the brown, reddish brown, and gray Carrara Formation. These formations are all Cambrian in age. The normal sequence is Zabriskie overlain by Carrara overlain by Bonanza King. On Google Earth, it looks like the Bonanza King and Zabriskie in the foreground are juxtaposed by a fault.

Okay! Let's move along! We've got to get through this canyon before...well, you're not supposed to camp in the canyon: It's day use only!! (This is really too bad, IMO; there is way too much to see along this road in one day.)

Here's another place I always end up stopping: on the road between White Pass and an unnamed pass between the two branches of upper Titanothere Canyon. We'll turn and look south down Titanothere Canyon.

Next time, maybe we'll make it to Red Pass!

A Few References:

Lengner, K., and Troxel, B.W., 2008, Death Valley's Titus Canyon & Leadfield ghost town: Deep Enough Press, 175 p.

Niemi, N.A., 2012, Geologic Map of the Central Grapevine Mountains, Inyo County, California, and Esmeralda and Nye Counties, Nevada: Nevada, Geological Society of America Digital Maps and Charts Series, DMC12, 1:48,000, 28 p. text.

Workman, J.B., Menges, C.M., Page, W.R., Taylor, E.M., Ekren, E. B., Rowley, P.D., Dixon, G.L., Thompson, RRA., and Wright, L.A., 2002, Geologic map of the Death Valley ground-water model area, Nevada and California: U.S. Geological Survey Miscellaneous Field Studies Map MF-2381-A, Pamphlet text, Sheet 1, Sheet 2.

Location map

Related Posts:

Beatty: Old Buildings, A Fold, and Onward toward Titus Canyon

The Approach to Titus Canyon: Amargosa Narrows, Bullfrog Pit, and the Original Bullfrog Mine

Mineral Monday: Close-Ups of Bullfrog Ore from the Original Bullfrog Mine, Nevada

The Approach to Titus Canyon: Tan Mountain

On this section of our trip, we are not actually in Titus Canyon: We are in some unnamed wash that drains eastward into the northwest part of the Amargosa Desert. Beyond "White Pass," we will at first be in the upper reaches of Titanothere Canyon, still not in Titus Canyon.

|

| A close-up of the same bush, showing the silky, tent-like mass in its branches. |

|

| Google Earth image of the Grapevine Mountains with a few labels. |

|

| (No labels on this one, though.) |

|

| Location of White Pass and other key localities, courtesy USGS TNM 2.0 Viewer. Labeling done in MS Paint. |

Between Tan Mountain and White Pass, the road runs south of several smallish dark brown hills composed of brown volcanic rock above white to pale yellow sedimentary rocks, often tuffacaceous, with intercalated tuffs. The brown, hill-capping formation has been mapped as Tlt, Lithic Ridge Tuff and related felsic rocks, by Workman et al (2002) and as part of Tw, the newly defined Wahguyhe Formation, by Niemi (2012). So it's a little confusing, but with a little research I determined that these brownish cliffs are indeed what has been called a latite flow before (Lengner and Troxel, 2008), with Niemi saying that the latite (he included it in the Wahguyhe) correlates with the Rhyolite of Picture Rock, which is rhyodacitic to latitic. So, when you look north at the dark brown caps, think rhyodacite to latite!

|

| Dark brown latite flow rock caps a hill north of the road. |

|

| I took this zoomed-in photo mostly because of the interesting patterns in the talus coming from our dark brown latite flow on the right (and, the sky!). |

|

| We're looking west from White Pass. The dark rocks to the left (S) are Cambrian; the rocks to the right (north) and straight ahead (W) are Tertiary. |

|

| The same photo, labeled with geologic formations (the Tertiary as shown is all from Niemi, 2012). |

Before leaving White Pass, we'll look off a little to the south. These two photos were taken about 7 years apart from almost the same spot. The lighting and clouds are a bit different, the time of day is nearly the same.

|

| Photo taken at about 10:00 am in late February, 2016. |

|

| Photo taken at about 10:30 am in early May, 2009. |

Okay! Let's move along! We've got to get through this canyon before...well, you're not supposed to camp in the canyon: It's day use only!! (This is really too bad, IMO; there is way too much to see along this road in one day.)

Here's another place I always end up stopping: on the road between White Pass and an unnamed pass between the two branches of upper Titanothere Canyon. We'll turn and look south down Titanothere Canyon.

|

| The alluvial fan in the distance is across Death Valley, beyond Stovepipe Wells. |

|

| At about the same point on the road, also looking to the south,you'll see Telescope Peak. |

|

| Telescope Peak (11,048 ft, 3367 m) is about 45 miles distant in this shot! |

A Few References:

Lengner, K., and Troxel, B.W., 2008, Death Valley's Titus Canyon & Leadfield ghost town: Deep Enough Press, 175 p.

Niemi, N.A., 2012, Geologic Map of the Central Grapevine Mountains, Inyo County, California, and Esmeralda and Nye Counties, Nevada: Nevada, Geological Society of America Digital Maps and Charts Series, DMC12, 1:48,000, 28 p. text.

Workman, J.B., Menges, C.M., Page, W.R., Taylor, E.M., Ekren, E. B., Rowley, P.D., Dixon, G.L., Thompson, RRA., and Wright, L.A., 2002, Geologic map of the Death Valley ground-water model area, Nevada and California: U.S. Geological Survey Miscellaneous Field Studies Map MF-2381-A, Pamphlet text, Sheet 1, Sheet 2.

Related Posts:

Beatty: Old Buildings, A Fold, and Onward toward Titus Canyon

The Approach to Titus Canyon: Amargosa Narrows, Bullfrog Pit, and the Original Bullfrog Mine

Mineral Monday: Close-Ups of Bullfrog Ore from the Original Bullfrog Mine, Nevada

The Approach to Titus Canyon: Tan Mountain

Location:

White Pass, Death Valley National Park, CA, USA

Labels:

california,

d.v.,

geology,

nevada,

parks,

plants,

road trip,

roadside,

sedimentary rocks,

tertiary,

titus,

volcanic rocks

Friday, June 17, 2016

Friday Field Photo: Cannonball Chert

Back in my eastern Nevada field days, I was lucky enough to go on a stratigraphy tour that took me to several good examples of chert nodules in the mostly Pennsylvanian Ely Limestone.

In the 1950s and 1960s, R. A. Breitrick and J. E. Welsh described the detailed stratigraphy of the Ely Limestone in the area of Ely and the Robinson mining district (with Breitrick, at least, continuing to work in the area to this day). They divided the formation into mappable units, W through C, bottom to top. (Their units A and B have since been placed in the overlying Permian Riepe Spring Limestone.) The only summary of this stratigraphy I could find online is shown here (pdf; Maher, 1995, p. 22).

Several units within the Ely, notably units S, R, P, L, and F, contain cannonball cherts (although I'm not sure about the details of units T, U, V, and W: I can't find my field sheets in the mess my office is currently in!). Theses photos are most likely from S, R, or P (my thoughts).

This is the best example I have of a chert nodule that is approaching "cannonball" in size and shape. Apparently, cannonball chert nodules can weather out and end up looking a lot like loose cannonballs. An excellent example of a loose cannonball nodule can be seen here [pdf] on page 27 (Maher, 1995, Fig. 7C).

These photos were taken in the spring of 2007 on the northeastern slopes of Rib Hill, a location that might or might not be accessible from Highway 50 or Route 6 via a side road formerly known as S.R. 44 or S.R. 485 (the location might be behind a locked gate).

|

| Nicely spherical chert nodules in the Ely Limestone, with 2.5 lb sledge for scale. |

Several units within the Ely, notably units S, R, P, L, and F, contain cannonball cherts (although I'm not sure about the details of units T, U, V, and W: I can't find my field sheets in the mess my office is currently in!). Theses photos are most likely from S, R, or P (my thoughts).

|

| Fairly large, sub-spherical chert nodule. |

These photos were taken in the spring of 2007 on the northeastern slopes of Rib Hill, a location that might or might not be accessible from Highway 50 or Route 6 via a side road formerly known as S.R. 44 or S.R. 485 (the location might be behind a locked gate).

Location:

Approx location in White Pine Co, NV

Labels:

44,

friday,

geology,

highway 50,

in the field,

nevada,

roadside,

route 6,

sedimentary rocks

Tuesday, June 14, 2016

The Approach to Titus Canyon: Tan Mountain

On our ongoing journey into Death Valley via Titus Canyon, we've left behind the Original Bullfrog mine (which can be seen from the road if you know where to look) and have made it past the eastern boundary of Death Valley National Park. As I've already mentioned, the Titus Canyon road can be distractingly washboardy in its early parts, and it's often barely wide enough for two vehicles to squeeze past each other, which only happens when a faster one wants to pass a slower one (it’s all one-way to the west).

In the photo, we're looking back the way we just came, which happens to be northward here, toward some low volcanic hills in the northwesternmost part of the Amargosa Desert.

By the way, I took all the photos in this post in early May, 2009. A lot of flowers were blooming in the upper Amargosa Desert and along the Titus Canyon road. We stopped often on that trip, for flowers, lizards, and short hikes. We didn’t stop as often during our February trip to Death Valley: We were intent on getting to the lower elevations to see the superbloom.

After about 50 minutes on the road, and about a half hour into the park (including flower-photo stops), MOH and I pulled over at a hill composed of exposed and outcropping ash-flow tuff. I found out later that this hill or butte is locally or colloquially known as “Tan Mountain.” It’s referred to by this name on Panoramio and in Death Valley's Titus Canyon & Leadfield Ghost Town by Lengner and Troxel (2002, 2008). The reason for the name is ... you guessed it, the color. It is not named on topo maps, and ordinarily, without knowing a local name, I'd call it hill 4915, for the 4915-foot marking shown on the Daylight Pass 7.5' quad (USGS TNM 2.0 location).

The road is widened somewhat at Tan Mountain, so it's easy to stop, look around, and go for a stroll. It can seem kind of warm on the slopes, even before ten in the morning; maybe the light-colored tuff reflects a lot of heat.

We continued to take flower photos as we rambled upward.

Nearing the base of the cliffs, I stopped to take this photo of an outcrop of the pumiceous, lithic-rich, poorly welded ash-flow tuff that makes up Tan Mountain. I didn't climb to the top of the hill, so I didn't get to see if the degree of welding changed significantly in the 200 feet or so to the top.

I'm not sure what ash-flow tuff formation this is. It was mapped as Tr--Pliocene to Oligocene felsic lava flows and tuffs by Workman et al (2002), and Lengner and Troxel (2008) implied that it erupted from the Timber Mountain caldera, although maybe they were intending, on page 63, to refer to tuff sheets seen a little farther to the west when they said:

Location map

Related Posts (in order of posting):

Death Valley, "Super" Blooms, Turtlebacks, and Detachments

Death Valley Trip, Part 2: More of the Badwater Turtleback Fault

Death Valley Trip, Part 3: Northward, and over Daylight Pass

Death Valley Trip, Getting There: Wave Clouds beyond the Sierra

Death Valley Trip, Getting There: A Hike to Pleistocene Shorelines

Death Valley Trip, Getting There: Walker Lake, Road Stories, A Bit about Copper, and Some Folds near Luning

Death Valley Trip, Getting There: A Jeep Trail, Folds and Cartoons of Folds, Even More Folds, and Boundary Peak

Death Valley Trip, Getting There: Highway 95, Redlich, Columbus Salt Marsh, and Another View of Boundary Peak

Death Valley Trip, Getting There: Coaldale, Black Rock, Lone Mountain, and the Boss Mine

Death Valley Trip, Getting There: Black Rock to Lida Junction to Beatty

Beatty: Old Buildings, A Fold, and Onward toward Titus Canyon

The Approach to Titus Canyon: Amargosa Narrows, Bullfrog Pit, and the Original Bullfrog Mine

Mineral Monday: Close-Ups of Bullfrog Ore from the Original Bullfrog Mine, Nevada

|

| Loose gravel typical of the Titus Canyon road east of Tan Mountain. |

By the way, I took all the photos in this post in early May, 2009. A lot of flowers were blooming in the upper Amargosa Desert and along the Titus Canyon road. We stopped often on that trip, for flowers, lizards, and short hikes. We didn’t stop as often during our February trip to Death Valley: We were intent on getting to the lower elevations to see the superbloom.

|

| Prickly pear cactus, which we saw along the road before entering the park (see location map way below). The cross-hatching pattern of the pads reminds me of the mineral alunite. |

|

| A close-up of the same plant. |

|

| An unidentified flowering plant with 1996 dime on the left for scale. |

The road is widened somewhat at Tan Mountain, so it's easy to stop, look around, and go for a stroll. It can seem kind of warm on the slopes, even before ten in the morning; maybe the light-colored tuff reflects a lot of heat.

|

| Tan Mountain, with geo-type hiker for scale. |

|

| An unknown yellow flowering plant with dime for scale. |

|

| Bright red fireweed on the slopes below the rounded spires and hoodoos of Tan Mountain. |

|

| A reddish brown lithic fragment in the poorly welded tuff. |

|

| Tent-like and hoodoo-like forms eroded into the ash-flow tuff. |

And that's how far we're going down the Titus Canyon road today."...you will see volcanic debris only from the Timber Mountain caldera on this trip."

Related Posts (in order of posting):

Death Valley, "Super" Blooms, Turtlebacks, and Detachments

Death Valley Trip, Part 2: More of the Badwater Turtleback Fault

Death Valley Trip, Part 3: Northward, and over Daylight Pass

Death Valley Trip, Getting There: Wave Clouds beyond the Sierra

Death Valley Trip, Getting There: A Hike to Pleistocene Shorelines

Death Valley Trip, Getting There: Walker Lake, Road Stories, A Bit about Copper, and Some Folds near Luning

Death Valley Trip, Getting There: A Jeep Trail, Folds and Cartoons of Folds, Even More Folds, and Boundary Peak

Death Valley Trip, Getting There: Highway 95, Redlich, Columbus Salt Marsh, and Another View of Boundary Peak

Death Valley Trip, Getting There: Coaldale, Black Rock, Lone Mountain, and the Boss Mine

Death Valley Trip, Getting There: Black Rock to Lida Junction to Beatty

Beatty: Old Buildings, A Fold, and Onward toward Titus Canyon

The Approach to Titus Canyon: Amargosa Narrows, Bullfrog Pit, and the Original Bullfrog Mine

Mineral Monday: Close-Ups of Bullfrog Ore from the Original Bullfrog Mine, Nevada

Location:

"Tan Mountain," Nevada, on Titus Canyon Road

Monday, June 6, 2016

Mineral Monday: Close-Ups of Bullfrog Ore from the Original Bullfrog Mine, Nevada

I collected this hand sample from the Original Bullfrog mine, Nye County, Nevada, sometime back in the mid to late 1980s when doing recon in the area, then cut and polished it—probably with a company saw and grinding wheel. This specimen is no doubt the best one I still have (a few may have been lost during one or two house moves), although it's been a while since I looked through all my rock boxes. This one photo has already been featured in two earlier posts, here and here.

I've got a few more photos to show you. These zoom in so we can see the size of the shiny ore minerals contained within the rock: v.g. (visible gold) and a silvery-gray silver mineral.

Well, it's hard to see them without holding the rock up to the light and waving it back and forth to get the metallic glint, so I've circled the little bits in yellow and light blue (cyan). Yellow is for gold; cyan is for silver.

Yes, these are very tiny flecks of native gold and a silver mineral. The silver mineral is probably either acanthite; Ag-bearing tetrahedrite, with Ag substituting for Cu in the solid-solution series with freibergite; or uytenbogaardtite.

Next time I get my hands on this sample—I think it's still up in Alaska—I'll see if I can get even better photos.

I've got a few more photos to show you. These zoom in so we can see the size of the shiny ore minerals contained within the rock: v.g. (visible gold) and a silvery-gray silver mineral.

|

| Here's the other side of this same rock. |

|

| We'll be focusing in on the lower left. |

|

| I've zoomed in here. Can you see the shiny flecks? |

|

| See them now? |

|

| Zooming in even farther, we can see the ore minerals without enlarging the photo. |

|

| A few of these show up really well. |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)